Verifying crash-recovery with lost buffered writes

Introduction

Writes to a RocksDB instance go through multiple layers before they are fully persisted. Those layers may buffer writes, delaying their persistence. Depending on the layer, buffered writes may be lost in a process or system crash. A process crash loses writes buffered in process memory only. A system crash additionally loses writes buffered in OS memory.

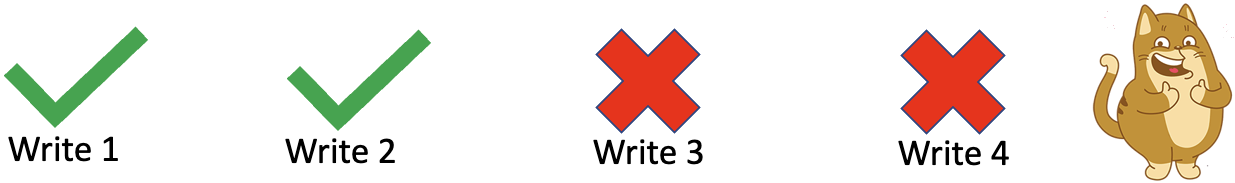

The new test coverage introduced in this post verifies there is no hole in the recovered data in either type of crash. A hole would exist if any recovered write were newer than any lost write, as illustrated below. This guarantee is important for many applications, such as those that use the newest recovered write to determine the starting point for replication.

Valid (no hole) recovery: all recovered writes (1 and 2) are older than all lost writes (3 and 4)

Invalid (hole) recovery: a recovered write (4) is newer than a lost write (3)

The new test coverage assumes all writes use the same options related to buffering/persistence.

For example, we do not cover the case of alternating writes with WAL disabled and WAL enabled (WriteOptions::disableWAL).

It also assumes the crash does not have any unexpected consequences like corrupting persisted data.

Testing for holes in the recovery is challenging because there are many valid recovery outcomes. Our solution involves tracing all the writes and then verifying the recovery matches a prefix of the trace. This proves there are no holes in the recovery. See “Extensions for lost buffered writes” subsection below for more details.

Testing actual system crashes would be operationally difficult. Our solution simulates system crash by buffering written but unsynced data in process memory such that it is lost in a process crash. See “Simulating system crash” subsection below for more details.

Scenarios covered

We began testing recovery has no hole in the following new scenarios. This coverage is included in our internal CI that periodically runs against the latest commit on the main branch.

- Process crash with WAL disabled (

WriteOptions::disableWAL=1), which loses writes since the last memtable flush. - System crash with WAL enabled (

WriteOptions::disableWAL=0), which loses writes since the last memtable flush or WAL sync (WriteOptions::sync=1,SyncWAL(), orFlushWAL(true /* sync */)). - Process crash with manual WAL flush (

DBOptions::manual_wal_flush=1), which loses writes since the last memtable flush or manual WAL flush (FlushWAL()). - System crash with manual WAL flush (

DBOptions::manual_wal_flush=1), which loses writes since the last memtable flush or synced manual WAL flush (FlushWAL(true /* sync */), orFlushWAL(false /* sync */)followed by WAL sync).

Issues found

- False detection of corruption after system crash due to race condition with WAL sync and `track_and_verify_wals_in_manifest

- Undetected hole in recovery after system crash due to race condition in WAL sync

- Recovery failure after system crash due to missing directory sync for critical metadata file

Solution details

Basic setup

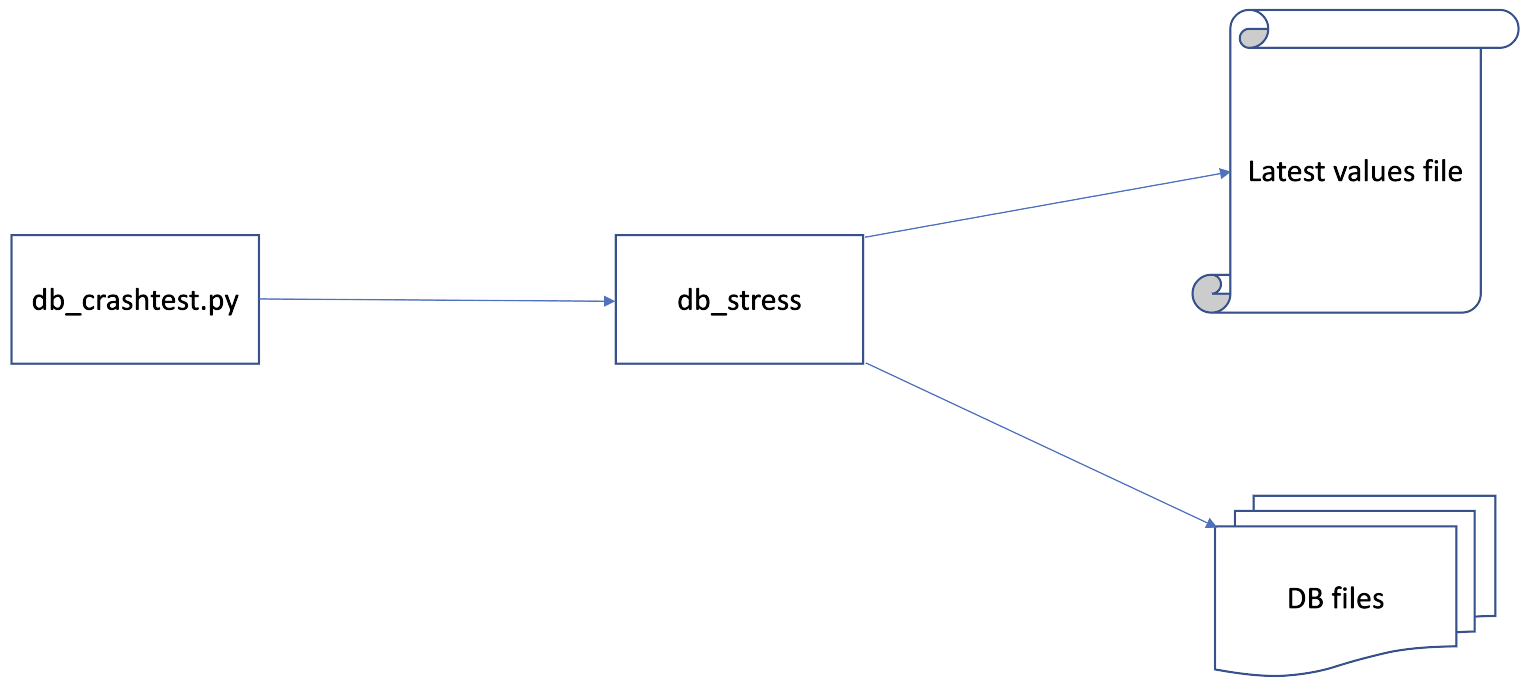

Our correctness testing framework consists of a stress test program (db_stress) and a wrapper script (db_crashtest.py).

db_crashtest.py manages instances of db_stress, starting them and injecting crashes.

db_stress operates a DB and test oracle (“Latest values file”).

At startup, db_stress verifies the DB using the test oracle, skipping keys that had pending writes when the last crash happened.

db_stress then stresses the DB with random operations, keeping the test oracle up-to-date.

As the name “Latest values file” implies, this test oracle only tracks the latest value for each key. As a result, this setup is unable to verify recoveries involving lost buffered writes, where recovering older values is tolerated as long as there is no hole.

Extensions for lost buffered writes

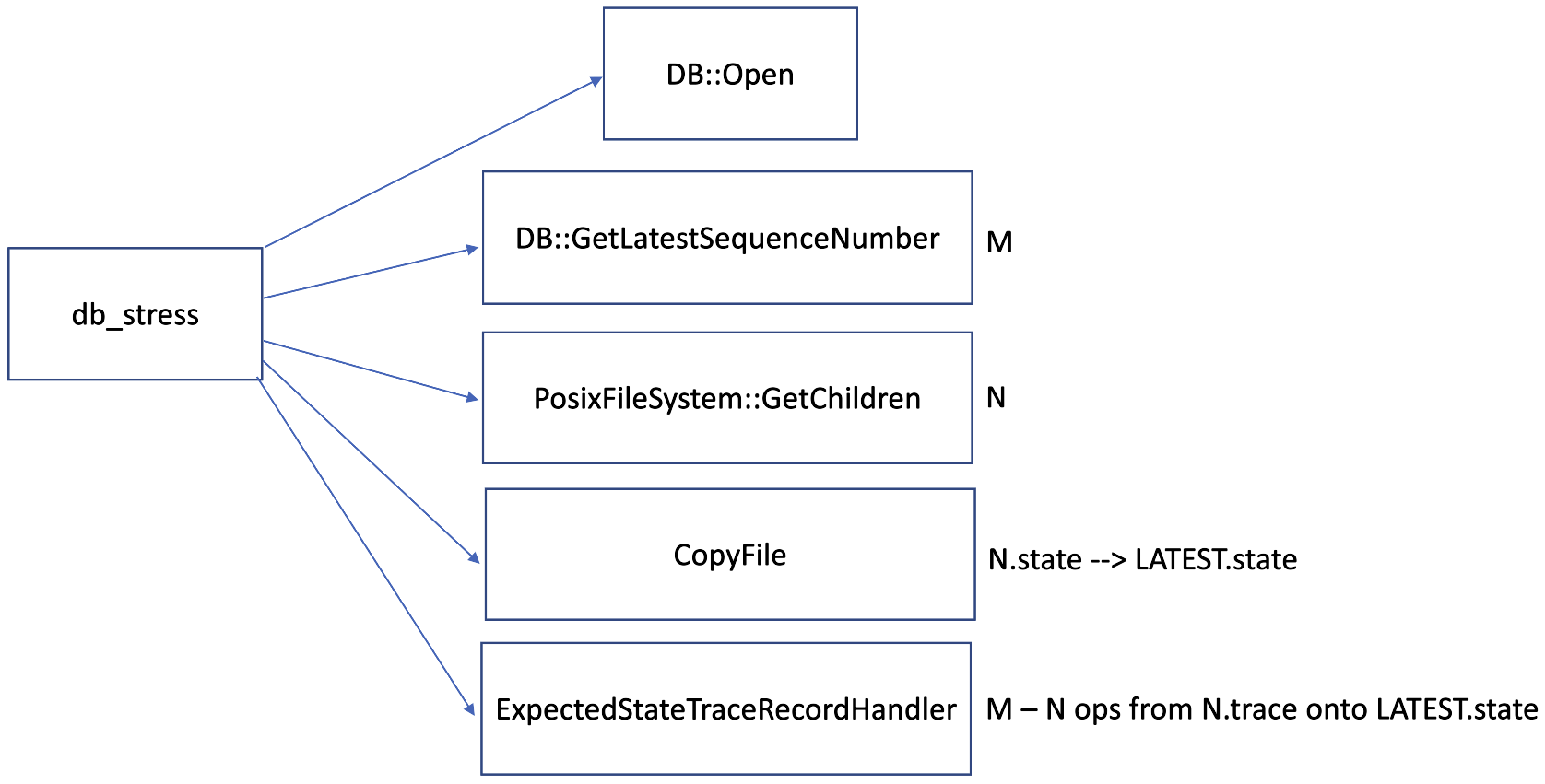

To accommodate lost buffered writes, we extended the test oracle to include two new files: “verifiedSeqno.state” and “verifiedSeqno.trace”.

verifiedSeqno is the sequence number of the last successful verification.

“verifiedSeqno.state” is the expected values file at that sequence number, and “verifiedSeqno.trace” is the trace file of all operations that happened after that sequence number.

When buffered writes may have been lost by the previous db_stress instance, the current db_stress instance must reconstruct the latest values file before startup verification.

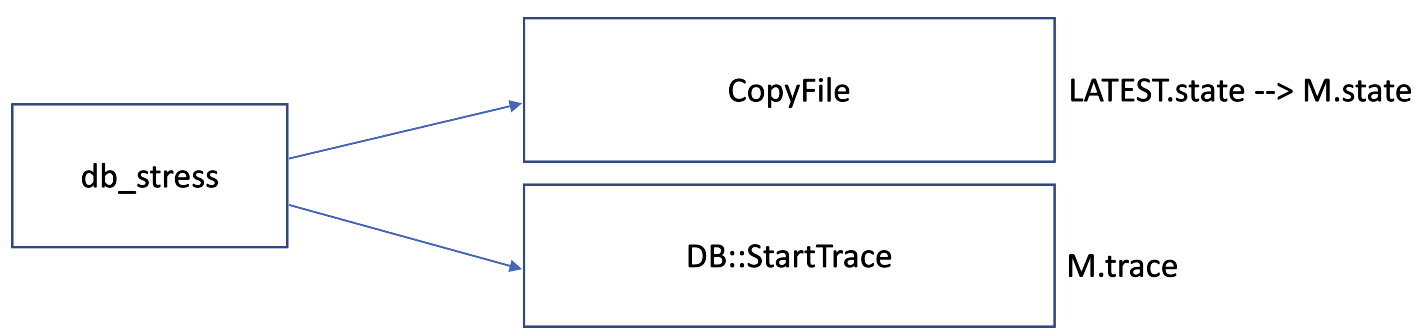

M is the recovery sequence number of the current db_stress instance and N is the recovery sequence number of the previous db_stress instance.

M is learned from the DB, while N is learned from the filesystem by parsing the “*.{trace,state}” filenames.

Then, the latest values file (“LATEST.state”) can be reconstructed by replaying the first M-N traced operations (in “N.trace”) on top of the last instance’s starting point (“N.state”).

When buffered writes may be lost by the current db_stress instance, we save the current expected values into “M.state” and begin tracing newer operations in “M.trace”.

Simulating system crash

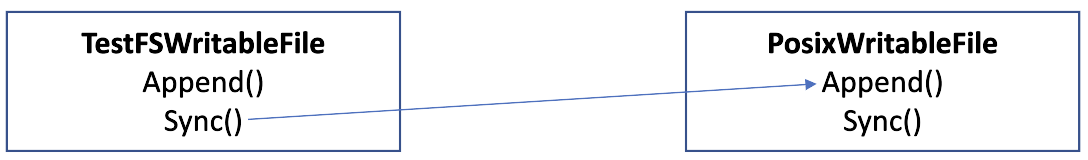

When simulating system crash, we send file writes to a TestFSWritableFile, which buffers unsynced writes in process memory.

That way, the existing db_stress process crash mechanism will lose unsynced writes.

TestFSWritableFile is implemented as follows.

Append()buffers the write in a localstd::stringrather than callingwrite().Sync()transfers the localstd::strings content toPosixWritableFile::Append(), which will thenwrite()it to the OS page cache.

Next steps

An untested guarantee is that RocksDB recovers all writes that the user explicitly flushed out of the buffers lost in the crash. We may recover more writes than these due to internal flushing of buffers, but never less. Our test oracle needs to be further extended to track the lower bound on the sequence number that is expected to survive a crash.

We would also like to make our system crash simulation more realistic. Currently we only drop unsynced regular file data, but we should drop unsynced directory entries as well.

Acknowledgements

Hui Xiao added the manual WAL flush coverage and compatibility with TransactionDB.

Zhichao Cao added the system crash simulation.

Several RocksDB team members contributed to this feature’s dependencies.