Java API Performance Improvements

RocksDB Java API Performance Improvements

Evolved Binary has been working on several aspects of how the Java API to RocksDB can be improved. Two aspects of this which are of particular importance are performance and the developer experience.

- We have built some synthetic benchmark code to determine which are the most efficient methods of transferring data between Java and C++.

- We have used the results of the synthetic benchmarking to guide plans for rationalising the API interfaces.

- We have made some opportunistic performance optimizations/fixes within the Java API which have already yielded noticable improvements.

Synthetic JNI API Performance Benchmarks

The synthetic benchmark repository contains tests designed to isolate the Java to/from C++ interaction of a canonical data intensive Key/Value Store implemented in C++ with a Java (JNI) API layered on top.

JNI provides several mechanisms for allowing transfer of data between Java buffers and C++ buffers. These mechanisms are not trivial, because they require the JNI system to ensure that Java memory under the control of the JVM is not moved or garbage collected whilst it is being accessed outside the direct control of the JVM.

We set out to determine which of multiple options for transfer of data from C++ to Java and vice-versa were the most efficient. We used the Java Microbenchmark Harness to set up repeatable benchmarks to measure all the options.

We explore these and some other potential mechanisms in the detailed results (in our Synthetic JNI performance repository)

We summarise this work here:

The Model

- In

C++we represent the on-disk data as an in-memory map of(key, value)pairs. - For a fetch query, we expect the result to be a Java object with access to the

contents of the value. This may be a standard Java object which does the job

of data access (a

byte[]or aByteBuffer) or an object of our own devising which holds references to the value in some form (aFastBufferpointing tocom.sun.unsafe.Unsafeunsafe memory, for instance).

Data Types

There are several potential data types for holding data for transfer, and they are unsurprisingly quite connected underneath.

Byte Array

The simplest data container is a raw array of bytes (byte[]).

There are 3 different mechanisms for transferring data between a byte[] and

C++

- At the C++ side, the method

JNIEnv.GetArrayCritical()allows access to a C++ pointer to the underlying array. - The

JNIEnvmethodsGetByteArrayElements()andReleaseByteArrayElements()fetch references/copies to and from the contents of a byte array, with less concern for critical sections than the critical methods, though they are consequently more likely/certain to result in (extra) copies. - The

JNIEnvmethodsGetByteArrayRegion()andSetByteArrayRegion()transfer raw C++ buffer data to and from the contents of a byte array. These must ultimately do some data pinning for the duration of copies; the mechanisms may be similar or different to the critical operations, and therefore performance may differ.

Byte Buffer

A ByteBuffer abstracts the contents of a collection of bytes, and was in fact

introduced to support a range of higher-performance I/O operations in some

circumstances.

There are 2 types of byte buffers in Java, indirect and direct. Indirect

byte buffers are the standard, and the memory they use is on-heap as with all

usual Java objects. In contrast, direct byte buffers are used to wrap off-heap

memory which is accessible to direct network I/O. Either type of ByteBuffer

can be allocated at the Java side, using the allocate() and allocateDirect()

methods respectively.

Direct byte buffers can be created in C++ using the JNI method

JNIEnv.NewDirectByteBuffer()

to wrap some native (C++) memory.

Direct byte buffers can be accessed in C++ using the

JNIEnv.GetDirectBufferAddress()

and measured using

JNIEnv.GetDirectBufferCapacity()

Unsafe Memory

The call com.sun.unsafe.Unsafe.allocateMemory() returns a handle which is (of course) just a pointer to raw memory, and

can be used as such on the C++ side. We could turn it into a byte buffer on the

C++ side by calling JNIEnv.NewDirectByteBuffer(), or simply use it as a native

C++ buffer at the expected address, assuming we record or remember how much

space was allocated.

A custom FastBuffer class provides access to unsafe memory from the Java side.

Allocation

For these benchmarks, allocation has been excluded from the benchmark costs by pre-allocating a quantity of buffers of the appropriate kind as part of the test setup. Each run of the benchmark acquires an existing buffer from a pre-allocated FIFO list, and returns it afterwards. A small test has confirmed that the request and return cycle is of insignificant cost compared to the benchmark API call.

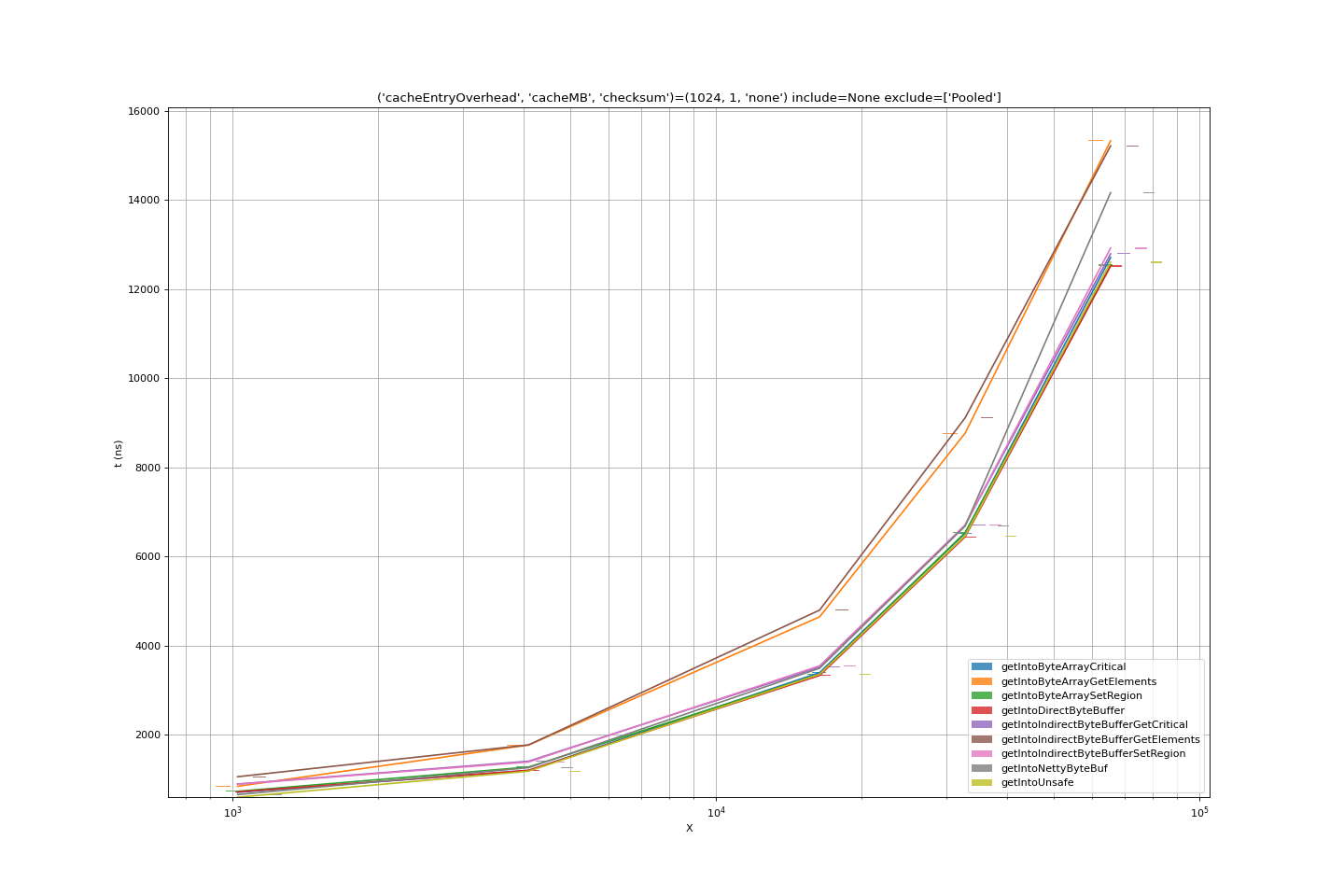

GetJNIBenchmark Performance

Benchmarks ran for a duration of order 6 hours on an otherwise unloaded VM, the error bars are small and we can have strong confidence in the values derived and plotted.

Comparing all the benchmarks as the data size tends large, the conclusions we can draw are:

- Indirect byte buffers add cost; they are effectively an overhead on plain

byte[]and the JNI-side only allows them to be accessed via their encapsulatedbyte[]. SetRegionandGetCriticalmechanisms for copying data into abyte[]are of very comparable performance; presumably the behaviour behind the scenes ofSetRegionis very similar to that of declaring a critical region, doing amemcpy()and releasing the critical region.GetElementsmethods for transferring data from C++ to Java are consistently less efficient thanSetRegionandGetCritical.- Getting into a raw memory buffer, passed as an address (the

handleof anUnsafeor of a nettyByteBuf) is of similar cost to the more efficientbyte[]operations. - Getting into a direct

nio.ByteBufferis of similar cost again; while the ByteBuffer is passed over JNI as an ordinary Java object, JNI has a specific method for getting hold of the address of the direct buffer, and using this, theget()cost with a ByteBuffer is just that of the underlying C++memcpy().

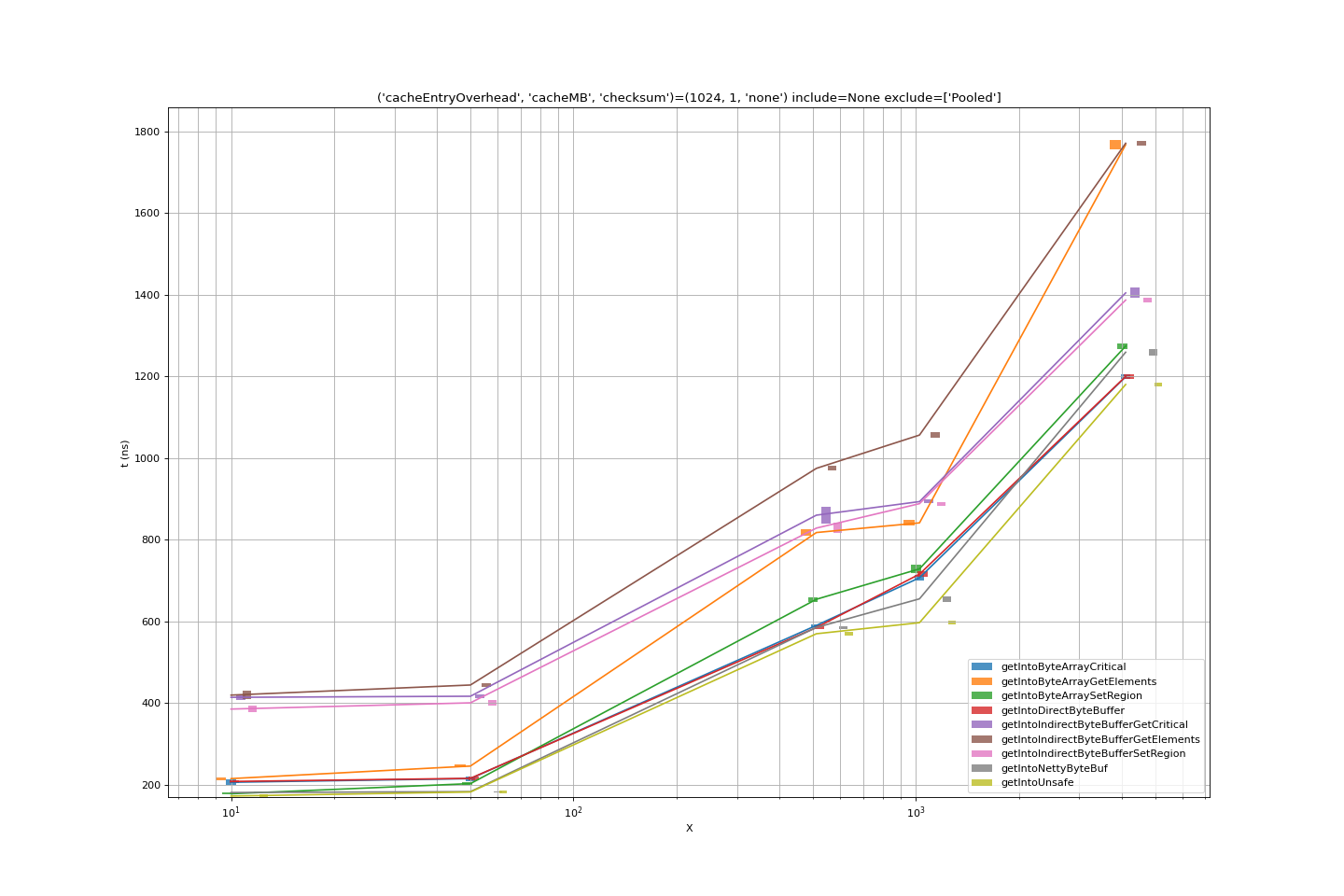

At small(er) data sizes, we can see whether other factors are important.

- Indirect byte buffers are the most significant overhead here. Again, we can

conclude that this is due to pure overhead compared to

byte[]operations. - At the lowest data sizes, netty

ByteBufs and unsafe memory are marginally more efficient thanbyte[]s or (slightly less efficient) directnio.Bytebuffers. This may be explained by even the small cost of calling the JNI model on the C++ side simply to acquire a direct buffer address. The margins (nanoseconds) here are extremely small.

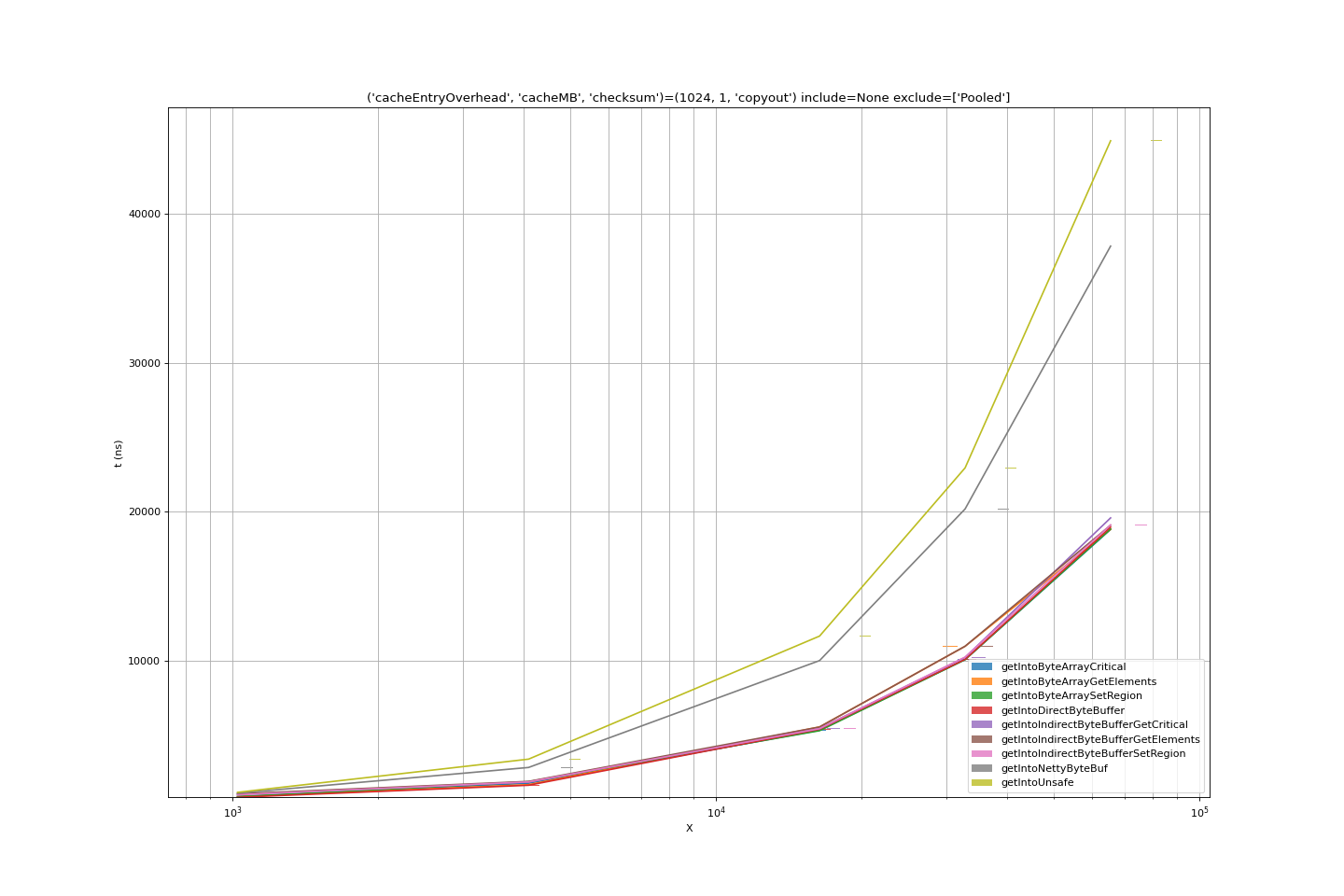

Post processing the results

Our benchmark model for post-processing is to transfer the results into a

byte[]. Where the result is already a byte[] this may seem like an unfair

extra cost, but the aim is to model the least cost processing step for any kind

of result.

- Copying into a

byte[]using the bulk methods supported bybyte[],nio.ByteBufferhave comparable performance. - Accessing the contents of an

Unsafebuffer using the supplied unsafe methods is inefficient. The access is word by word, in Java. - Accessing the contents of a netty

ByteBufis similarly inefficient; again the access is presumably word by word, using normal Java mechanisms.

PutJNIBenchmark

We benchmarked Put methods in a similar synthetic fashion in less depth, but enough to confirm that the performance profile is similar/symmetrical. As with get() using GetElements is the least performant way of implementing transfers to/from Java objects in C++/JNI, and other JNI mechanisms do not differ greatly one from another.

Lessons from Synthetic API

Performance analysis shows that for get(), fetching into allocated byte[] is

equally as efficient as any other mechanism, as long as JNI region methods are used

for the internal data transfer. Copying out or otherwise using the

result on the Java side is straightforward and efficient. Using byte[] avoids the manual memory

management required with direct nio.ByteBuffers, which extra work does not

appear to provide any gain. A C++ implementation using the GetRegion JNI

method is probably to be preferred to using GetCritical because while their

performance is equal, GetRegion is a higher-level/simpler abstraction.

Vitally, whatever JNI transfer mechanism is chosen, the buffer allocation

mechanism and pattern is crucial to achieving good performance. We experimented

with making use of netty’s pooled allocator part of the benchmark, and the

difference of getIntoPooledNettyByteBuf, using the allocator, compared to

getIntoNettyByteBuf using the same pre-allocate on setup as every other

benchmark, is significant.

Equally importantly, transfer of data to or from buffers should where possible be done in bulk, using array copy or buffer copy mechanisms. Thought should perhaps be given to supporting common transformations in the underlying C++ layer.

API Recommendations

Of course there is some noise within the results. but we can agree:

- Don’t make copies you don’t need to make

- Don’t allocate/deallocate when you can avoid it

Translating this into designing an efficient API, we want to:

- Support API methods that return results in buffers supplied by the client.

- Support

byte[]-based APIs as the simplest way of getting data into a usable configuration for a broad range of Java use. - Support direct

ByteBuffers as these can reduce copies when used as part of a chain ofByteBuffer-based operations. This sort of sophisticated streaming model is most likely to be used by clients where performance is important, and so we decide to support it. - Support indirect

ByteBuffers for a combination of reasons:- API consistency between direct and indirect buffers

- Simplicity of implementation, as we can wrap

byte[]-oriented methods

- Continue to support methods which allocate return buffers per-call, as these are the easiest to use on initial encounter with the RocksDB API.

High performance Java interaction with RocksDB ultimately requires architectural decisions by the client

- Use more complex (client supplied buffer) API methods where performance matters

- Don’t allocate/deallocate where you don’t need to

- recycle your own buffers where this makes sense

- or make sure that you are supplying the ultimate destination buffer (your cache, or a target network buffer) as input to RocksDB

get()andput()calls

We are currently implementing a number of extra methods consistently across the Java fetch and store APIs to RocksDB in the PR Java API consistency between RocksDB.put() , .merge() and Transaction.put() , .merge() according to these principles.

Optimizations

Reduce Copies within API Implementation

Having analysed JNI performance as described, we reviewed the core of RocksJNI for opportunities to improve the performance. We noticed one thing in particular; some of the get() methods of the Java API had not been updated to take advantage of the new PinnableSlice methods.

Fixing this turned out to be a straightforward change, which has now been incorporated in the codebase Improve Java API get() performance by reducing copies

Performance Results

Using the JMH performances tests we updated as part of the above PR, we can see a small but consistent improvement in performance for all of the different get method variants which we have enhanced in the PR.

1

java -jar target/rocksdbjni-jmh-1.0-SNAPSHOT-benchmarks.jar -p keyCount=1000,50000 -p keySize=128 -p valueSize=1024,16384 -p columnFamilyTestType="1_column_family" GetBenchmarks.get GetBenchmarks.preallocatedByteBufferGet GetBenchmarks.preallocatedGet

The y-axis shows ops/sec in throughput, so higher is better.

Analysis

Before the invention of the Pinnable Slice the simplest RocksDB (native) API Get() looked like this:

1

2

3

Status Get(const ReadOptions& options,

ColumnFamilyHandle* column_family, const Slice& key,

std::string* value)

After PinnableSlice the correct way for new code to implement a get() is like this

1

2

3

Status Get(const ReadOptions& options,

ColumnFamilyHandle* column_family, const Slice& key,

PinnableSlice* value)

But of course RocksDB has to support legacy code, so there is an inline method in db.h which re-implements the former using the latter.

And RocksJava API implementation seamlessly continues to use the std::string-based get()

Let’s examine what happens when get() is called from Java

1

2

3

4

jint Java_org_rocksdb_RocksDB_get__JJ_3BII_3BIIJ(

JNIEnv* env, jobject, jlong jdb_handle, jlong jropt_handle, jbyteArray jkey,

jint jkey_off, jint jkey_len, jbyteArray jval, jint jval_off, jint jval_len,

jlong jcf_handle)

- Create an empty

std::string value - Call

DB::Get()using thestd::stringvariant - Copy the resultant

std::stringinto Java, using the JNISetByteArrayRegion()method

So stage (3) costs us a copy into Java. It’s mostly unavoidable that there will be at least the one copy from a C++ buffer into a Java buffer.

But what does stage 2 do ?

- Create a

PinnableSlice(std::string&)which uses the value as the slice’s backing buffer. - Call

DB::Get()using the PinnableSlice variant - Work out if the slice has pinned data, in which case copy the pinned data into value and release it.

- ..or, if the slice has not pinned data, it is already in value (because we tried, but couldn’t pin anything).

So stage (2) costs us a copy into a std::string. But! It’s just a naive std::string that we have copied a large buffer into. And in RocksDB, the buffer is or can be large, so an extra copy something we need to worry about.

Luckily this is easy to fix. In the Java API (JNI) implementation:

- Create a PinnableSlice() which uses its own default backing buffer.

- Call

DB::Get()using thePinnableSlicevariant of the RocksDB API - Copy the data indicated by the

PinnableSlicestraight into the Java output buffer using the JNISetByteArrayRegion()method, then release the slice. - Work out if the slice has successfully pinned data, in which case copy the pinned data straight into the Java output buffer using the JNI

SetByteArrayRegion()method, then release the pin. - ..or, if the slice has not pinned data, it is in the pinnable slice’s default backing buffer. All that is left, is to copy it straight into the Java output buffer using the JNI SetByteArrayRegion() method.

In the case where the PinnableSlice has succesfully pinned the data, this saves us the intermediate copy to the std::string. In the case where it hasn’t, we still have the extra copy so the observed performance improvement depends on when the data can be pinned. Luckily, our benchmarking suggests that the pin is happening in a significant number of cases.

On discussion with the RocksDB core team we understand that the core PinnableSlice optimization is most likely to succeed when pages are loaded from the block cache, rather than when they are in memtable. And it might be possible to successfully pin in the memtable as well, with some extra coding effort. This would likely improve the results for these benchmarks.